Monticello Teacher Exposes Her Students to the Engineering Process Via a PrIMES- and POETS-Developed Curriculum

Feburary 20, 2019

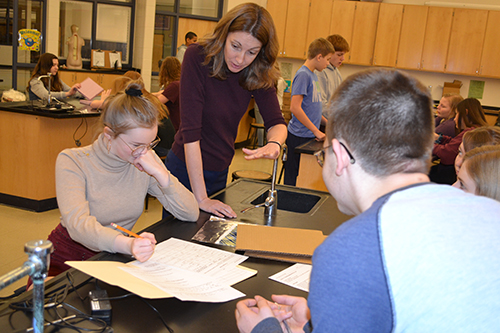

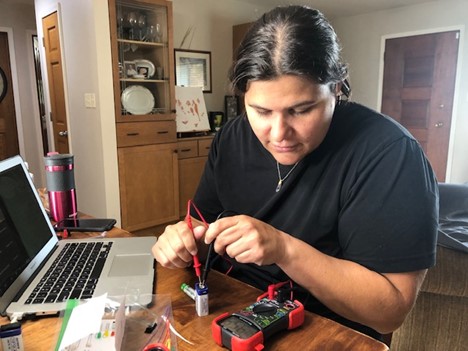

Jennifer Smith speaking with her students as they work on their incubator project.

For the last month or so, eighth graders in Jennifer Smith’s class at Monticello Middle School have been learning a whole lot about what being an engineer might be like. They’ve been designing infant incubators as part of a month-long curriculum Smith helped design when she participated in the PrIMES (Practices integrating Math, Engineering, and Science) program, an ISBE grant developed by Barbara Hug, Sammy Lindgren, Sue Gasper, and Megan McCleary, along with POETS' Education Coordinator Joe Muskin. While working on the curriculum, her students have not just learned some science and about the engineering process; they’ve also experienced what working on a team is like and that engineers can make a difference in people's lives.

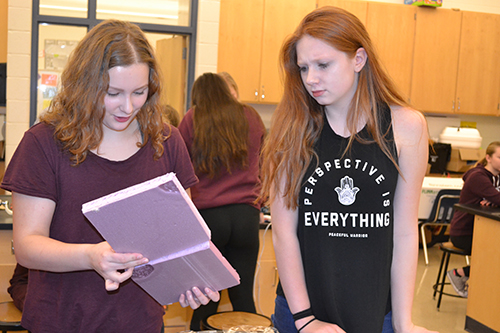

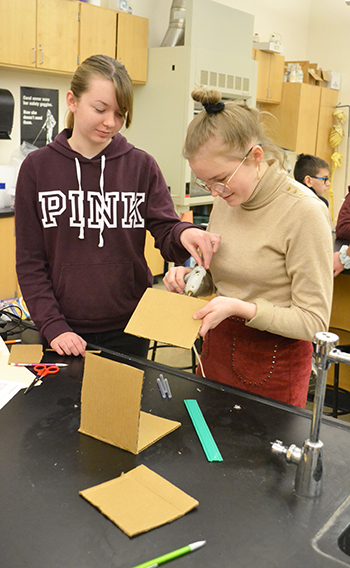

Two Monticello Middle School students begin constructing their incubator.

POETS (Power Optimization for Electro-Thermal Systems), an NSF-funded Engineering Research Center has been involved with the curriculum from the beginning, including helping fund the first implementation under PrIMES. The goal of the curriculum, addressing a real-world, heat-related problem, closely aligns with the Center’s goals: to develop innovations related to heat that provide “more power in less space” and which have the potential to impact our everyday lives. And that’s exactly what the curriculum was about—designing an inexpensive incubator that can regulate a baby’s body temperature. So although PrIMES ended about a year ago, POETS is going to continue developing the curriculum. In fact, Jennifer Smith and the rest of her team from PrIMES will be participating in POETS RET this coming year.

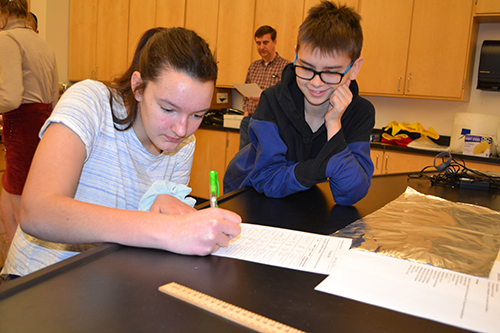

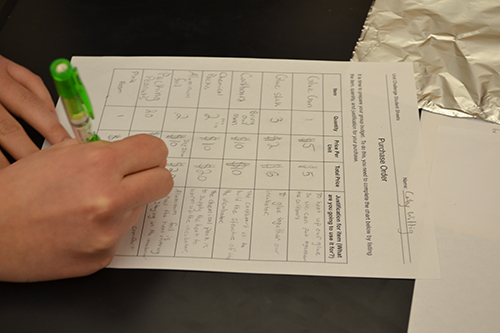

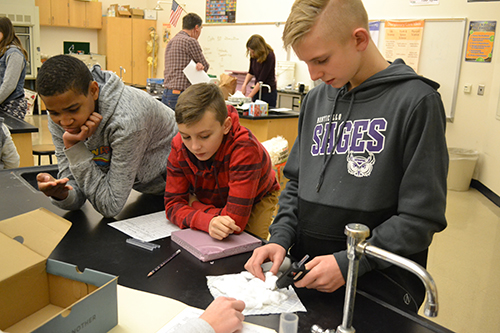

Above: Agroup of students preparing the budget for their incubator.

Below: A student works on the dreaded budget for her team.

The challenge in regards to designing the infant incubator was to make one without using electricity, which sometimes doesn’t exist in more remote locations, or solar heat, which can be very expensive, but instead to use chemical reactions that produce a certain level of heat that can be sustained for a long period of time.

Smith says she got involved with PRIMES in order to “find a good solid way to bring more engineering into my classroom, because it’s a big part of the Next Generation Science Standards.” She also wanted to ensure that her students had an opportunity to practically apply the science content that they were learning by trying to engineer things. Plus, she admits, “It’s fun for the kids.”

Do her students realize that what they’ve been doing is engineering?

“They do, she acknowledges, “because we’ve talked about the different steps, and we talk about what engineers do.” When designing the curriculum, she also attempted to make sure that it emphasized the engineering process. “That’s one of the reasons that we have a budget; that’s one of the reasons that they have a design plan; it’s one of the reasons they prototype, and prototype, and prototype. So they understand the process,” she explains.

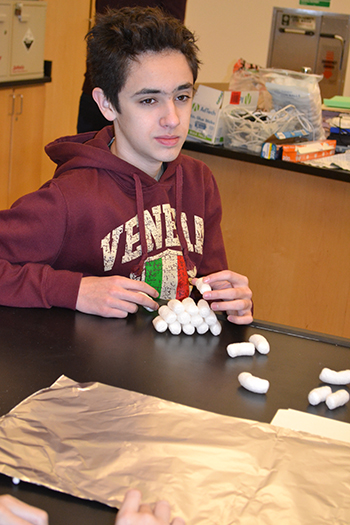

A Monticello Middle School student collects the foam they will use to make their incubator.

Two students hot glueing their incubator.

Two students hot glueing their incubator. While preparing and sticking to a budget is an important part of the engineering process, she reports that it was one of her students’ least favorite aspects of the project. “They don’t like that,” she admits.

Another key emphasis was learning to work as a team. Smith acknowledges that teamwork is an important aspect of engineering and shares the benefit of the incubator project in terms of teamwork and collaboration. “Engineers work together on teams,” she stresses, then explains how they went about fostering that. “They each had their own designs to start out with and what materials they wanted to use, and then they had to come to a group consensus, and then they had to come to reality with the budget.”

Knowing the likelihood that one or more people in a group will just naturally tend to take over, she built something into the curriculum to prevent that. Thus each team created a plan detailing “who’s responsible for what aspect of the building to ensure that everybody is building and not one person is taking over what they do,” she explains. “But it’s super important to try to build cohesive ways for students to collaborate with each other, which is sometimes difficult. And so we spend a lot of time on that.”

When it comes to a real-world project that is well aligned to all that the curriculum was intended to impart to students, the infant incubator is brilliant. It’s got the human component; it’s serving people. It's multidisciplinary; it teaches the students about chemical reactions but it's also got engineering design and building a prototype; it’s also got a budget. So it incorporates several different disciplines. How did Smith and her POETS RET cohorts come up with that?

Smith admits that their initial curriculum design involved building an incubator for turtle eggs, then credits Joe Muskin with steering them in the direction of doing incubators for infants, acknowledging that, “While the turtle incubator was fun, there’s not as much of a demand or a need for that.”

Smith claims her students seemed to have bought into the whole, ‘We get to help people through this” notion. However, she also didn’t want her students to see it as an “us and them” situation. “I don’t want to create that dichotomy,” she stresses.

So one of the things that she’s talked about with her students is that there are people throughout the world and also in the United States who may not have access to electricity or incubators.

“So I want them to see it as the global issue that it is, but also to bring light to medical access and things in underdeveloped nations. I want them to see that we have hospitals, and we have easy access to get to a hospital, but that’s not the case everywhere.”So she has sought to ensure that her students are being respectful of other cultures and other ideas. “Other ways of life are important too.”

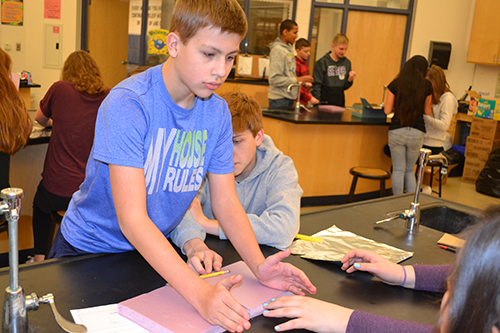

A group attempts to decide on the dimensions of the foam for their incubator

Joe Muskin and Jennier Smith discuss the project.

In addition to developing a great curriculum to teach to her kids, Smith explains that, personally, being in the program gave her "permission to try and fail, I think,” she explains. And like her students, she and the other teachers also enjoyed the collaboration. “So a group of teachers passionate about an idea and wanting to try something out and being able to collaborate and build off of each other for that.”

She adds that POETS has also done a really good job of helping with the materials, and things public educators sometimes have difficulty accessing. When the ChromeBooks her students had access to didn’t have the necessary software on them, Muskin lent them laptops with the proper software. “So being able to use the materials like that has given us a wider range of activities that we can do,” she explains.

Smith adds that the incubator curriculum had been a great project, and she was excited for the students to test their designs, to “see what we come up with and how they might redesign. These tend to be the things that they remember the most, so that’s important.”

Regarding whether any of her students might end up being engineers in the future, Smith claims, “I think every student has different skills; I think they all have the potential to be engineers, different types of engineers.”

She even has concrete proof that exposing her students to engineering has impacted them. She reports that when she visited the high school recently, one of her former students who had worked on some of her engineering projects in 8th grade told her that she’s decided to become a mechanical engineer. “So that was pretty exciting to hear that. So you never know; you never know who or when they might decide.”

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: 6-8 Outreach, POETS, RET, 2019

For additional articles about POETS, see:

- Dr. Howard Fourth Graders Learn Engineering, Problem-Solving, While Building Solar Cars

- POETS’ Education Program Introduces Students of All Ages to Interdisciplinary Research in Electro-Thermal Systems

- POETS Seeks to Change the Attitudes, Shape of Students in the STEM Pipeline

- POETS, New NSF Center at Illinois, Poised to Revolutionize Electro-Thermal Systems

Jennier Smith shows Joe Muskin the MMS "cash" her students used for the project; the $100 bills have her picture on them.

A Monticello Middle School student glues some insulating material to his team's incubator.

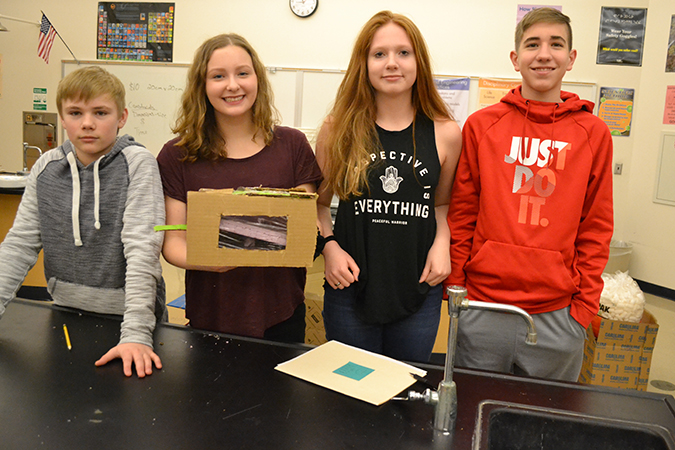

A group of students with their completed incubator, which includes side windows so caregivers can see the baby inside.

A group of students with their completed incubator, which includes side windows so caregivers can see the baby inside.

.jpg)